Research visit to the “Bethlem Museum of the Mind” & Bethlem Hospital Archive London, April, 2015.

A suburban train takes me to “Eden Park”, not only by name an idyllic village in the south-eastern periphery of London. In the back streets the cherry trees are in full bloom. I cross a creek and walk along the fence of an open space that resembles a huge park until I reach the entrance of Bethlem Royal Hospital. The “Bethlem Museum of the Mind” and its archive are located on the grounds of the psychiatric hospital that is still in operation, after a long history that dates back into the twelfth century. The representative central building of this complex that was inaugurated in 1930 has just recently been opened as the new museum. Here archivist and curator Colin Gale awaits me behind the reception desk. We have a chat about the institution and the museum, especially in late nineteenth century when Francis Galton visited the clinic and commissioned portraits of patients for his photographic experiments with the composite technique.

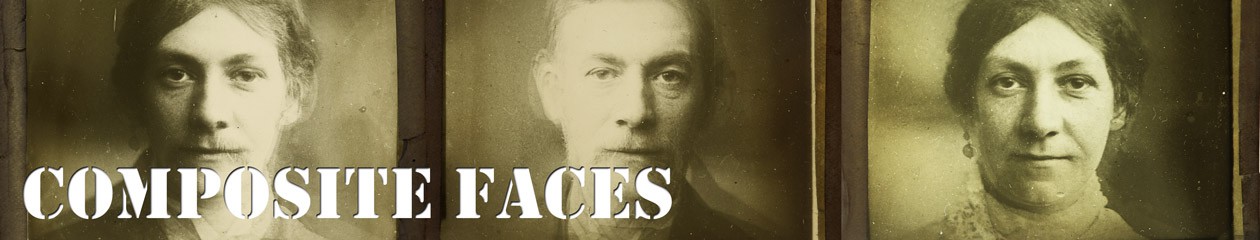

The portraits of 76 male and 65 female patients are preserved among the “Galton Papers” at the Special Collections of University College London. The frontal, half-length portraits carry a number as well as family names. The archive at Bethlem holds the admission and discharge books as well as the medical files. By comparing the periods of treatment of different patients, who were often also photographed as part of the asylum’s procedure, the photos in the “Galton Papers” can be dated to 1880-1882. Also, not only names, but information on age, profession, family history, as well as the diagnosis notes on the treatment of the mental illness can be drawn from the material. The entries tell veritable stories of the life and fate of the individuals that were used as source material for Galton’s experiments with the composite technique. And while composite portraiture was aimed at de-individualising and typifying, these documents give back an identity and personality to the objects of study. Furthermore the photographs and the material kept at Bethlem Hospital, provide insight into the disciplinary institutions and their policies, modes of categorisation and typification of their clients, often by visual means.

In the lunch break and after my visit to the museum and archive I have the chance to walk around the hospital site. The institution is set in a huge green area; there are several buildings for all kinds of purposes, cafeterias, gardens, orchards, sport facilities, but also enclosed highly guarded buildings. But generally most doors seem to be open, patients, staff and visitors walk around the park and the atmosphere is pleasant.

Photography in Bethlem

Even before Galton and his anonymous photographer entered the institution, Bethlem had a history of photographic practice. In the late1850’s, Henry Hering, a professional photographer who had his studio in London’s Regent Street, produced portraits of patients of Bethlem Asylum. Several individuals were photographed shortly after their admittance and at a later stage, before their release. These highly staged before-and-after images tell interesting stories, about the representation and perception of madness (ruffled hair, disfigured face and twisted body) as well as about moral treatment and the possibility to regain social respectability. One of Hering’s Bethlem portraits, produced in 1858-59, found its way into the collection of photographs that was compiled by Charles Darwin for his studies on facial expression. The book “The Expressions of the Emotions in Man and Animals” (1872) could be described as a reference for Galton’s experiments with photography and composite portraiture in particular.

Even though the composite portraits of Bethlem and Hanwell patients were never published and the results are not bequeathed, the experiments represent an important stage in Galton’s development of the composite technique, especially in relation to the representation of “visual pathologies” that led to composites and publications on tuberculosis at a later stage. It is surprising that Galton had so many portraits taken in Bethlem and Hanwell Asylum and did not push on with his experiments to the stage of publication or even preserving the experiments with the photos he undoubtedly conducted. The “Galton Papers” at UCL Special Collections hold most of the portraits as duplicates, even triplicates and the UCL “Galton Collection” the corresponding glass negatives.

Bethlem in Late Nineteenth-Century

In eighteenth and early nineteenth century Bethlem became the embodiment for the notoriously misanthropic lunatic asylum, it was known for maltreatment and long-term confinement of its patients and their public exhibition. Through public pressure it was eventually put under state supervision in the 1850’s. This process of reform that started in the 1840’s went along with a shift away from force and physical restraint to moral therapy and an opening of the institution. In mid- and late nineteenth century Bethlem, at least in the public halls, resembled more a gentlemen’s club, rather than a clinic and it received favorable reports from the official supervisors. However around 1880, the time when Galton’s photographs were taken in Bethlem, the advocates of moral therapy were losing ground and a new pharmaceutical regime entered the institution. Drug treatment increased, new forms of medical restraint became possible and Bethlem again was criticised for its seclusion practices and a high rate of suicides.[1]

When looking at the portraits commissioned by Galton of it is easy to imagine the pressure put on the patients to comply with the procedure of being photographed, also most likely some were under strong medication. Most patients conform to the rules dictated by composite portraiture: to keep the head still and straight, as well as to look into the camera with a neutral expression; some, however, look away or pull faces, this might be due to their mental condition, but could also be a deliberate subversion of the process of recording of their features.

Museum of the Mind

After visiting the exhibition I meet Colin Dale again and we speak about the “Museum of the Mind”, the exhibition architecture and the presentation of artifacts. The new museum has just opened, in February 2015, after a re-conceptualisation period of 2-3 years. The choice not to present the collection chronologically was taken in reluctance to conform to ideas of linear progress and to clarify that the primary aim was not a historical excursion of Bethlem’s history. Six themes were chosen where historical and contemporary exhibits are contrasted, while the focus lies on the period from early 19th century until today. For instance the theme of labeling, of producing and ascribing psychiatric diagnoses, includes objects and texts from different periods of Bethlem’s history. It is aimed at asking questions on the language used in relation to mental disease and the stigma attached to this diagnosis, ends are deliberately left open and questions are rather raised than answered. Also the photographic practices in nineteenth century Bethlem are presented, but these disciplinary portraits are contrasted with a contemporary artistic position, a series of photographs that in a gentle and dialogic manner portrays people with psychic problems.

Apart from instruments and historical documents also video installations try to provide a diachronic access to the topic of mental health and a large number of artworks by patients of different periods are exhibited. The paintings and drawings are highly interesting finding another language for the feelings and emotions and the mental instabilities that the patients were experiencing. The contrast to the language of medical classification and the neutral descriptions of behaviour and improvement could not be stronger. The core of this alternative perception and evaluation constitutes a central space of the museum that is designed as sort of a recreation area; here the walls are filled with the creative output of generations of patients.

Colin Dale tells me about the difficulties of choosing from the huge collection and the handling of certain items such as instruments of restraint and the reconstruction of a padded cell. Here distance and openness guided the curatorial decisions: iron manacles and other devices of confinement are presented in thickly framed cases that stand back compared to the other exhibition architecture, the items are receding towards the wall, rather than sticking out prominently as sort of a horror show. The padded cell is not installed as a confined space, but in sections and opening towards the well-lit external rooms with big windows that are facing the green hospital grounds. Dale tells me that the curators have visited many institutions in Europe, among others In Gent, Belgium and Göppingen, Germany as inspiration and before finalising their permanent exhibition. These decisions as well as placing the new museum so prominently on the site of the Hospital still in use pursuit the goal of drawing various groups of visitors, such as local people, external visitors, staff and patients, to the museum and onto the site of the hospital that still meets with lots of prejudice.

Bethlem Gallery

In the same vein of bringing together patients and a wider public, on the ground floor a Bethlem Gallery is installed that shows contemporary artworks of current and former patients. It also includes studio facilities where clients can work creatively, supported by staff specialised in art education and art therapy.

[1] See: Andrews, Jonathan et al.: The History of Bethlem. London/New York: Routledge, 1997; & Dale, Colin; Howard, Robert: Presumed Curable. An Illustrated Casebook of Victorian Psychartric Patients in Bethlem Hospital. Petersfield/Philadephia: Wrightson Biomedical Publishing, 2003.